Review by Jessica Goodfellow

PANK Books / April 2020 / 92 pages

For a poetry collection with the theme of female aging, could there be any form more apt than a hybrid collection? Shira Dentz’s sixth book Sisyphusina, winner of the Eugene Paul Nassar Poetry Prize from Utica College, is a startling hybrid work that forces us to ask this question. Dentz, in an interview with Dexter Booth for Waxwing, explained: “I’m interested in giving voice to psychic experiences for which our language lacks words. All languages lack words for a variety of experiences—who and what get to have language is connected to power structures. An example I often use is that there’s no female equivalent word for ‘castrated’ or ‘emasculated.’” In the absence of a vocabulary for a myriad of female experiences, Dentz employs photographs, scatter plots, drawings, photocopies, collages, and even a musical collaboration to give expression to the reality, both personal and social, both biological and emotional, of aging as a modern woman.

How many poems there are about male aging in the canon? Their proliferation makes the implicit assumption that the male experience is the default for aging. For example, searching the Academy of American Poets website yields twenty-four example poems on the topic, only two of which are by women. Where are the poems about menopause, the loss of conventional beauty markers, and the invisibility of the aging woman in society? Dentz, in seeking to make room for such female experiences, finds that exploring and bending space is a necessary response, as is the augmentation of words with images and music.

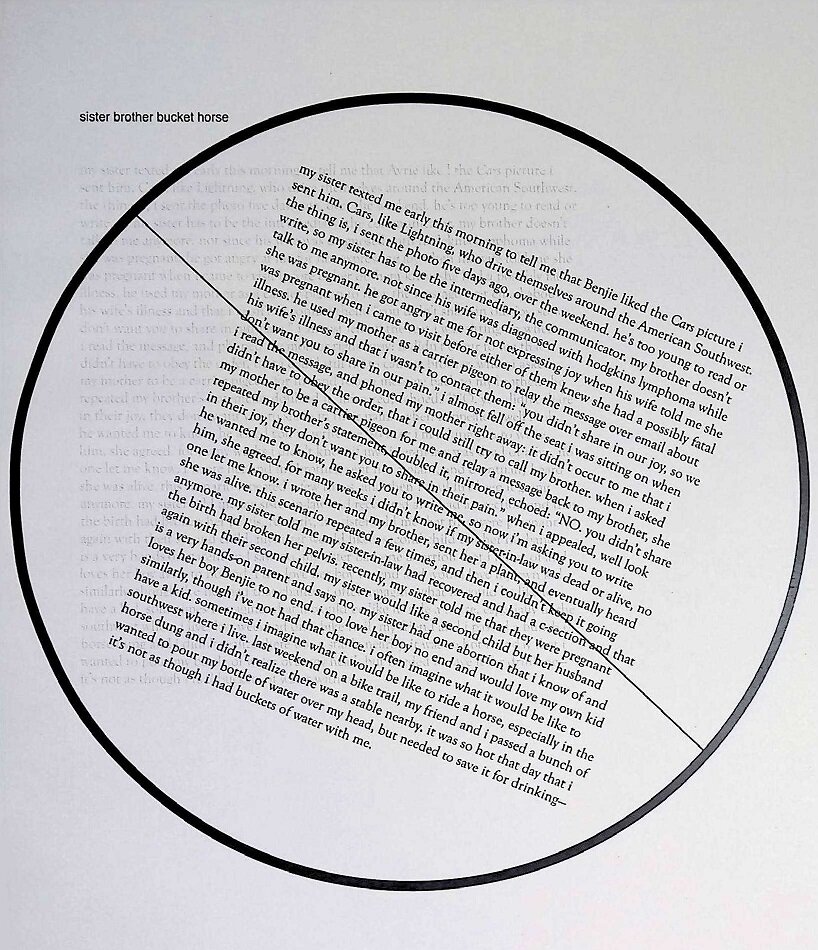

Dentz’s determined decentering of the canon in order to make room for women’s experiences is directly reflected in her radical, topsy-turvy carving of space. For example, in “Roses of the Organic,” she places a rounded pyramid of words at the top of the page, followed by standard left-aligned paragraphs, while on the right side of the page, a justified column of words runs up and down, the top paragraph in italics, the rest not. In “sister brother bucket horse,” the text is in light gray shadow where you’d expect it to be on a conventional page, but superimposed is that same text now in a black font, the entire block of which has been displaced slightly from the left margin and then rotated about 25 degrees or so to the right, then circumscribed by a black circle with its diameter drawn on an axis not shared with either rendering of the text.

Is this a little difficult to read? No more difficult than it is to be an aging woman in a society that values youth and beauty over wisdom and experience. Which is to say: this is not your traditional left-aligned male-centered text for a reason. Are these texts visually disorienting? No more than the hormonal changes of midlife disorient a mind in an unrecognizably aging body.

There seems to be no element of bookmaking that Dentz doesn’t consciously consider. Font, too, is not conventionally consistent. Lines in all caps or in larger font jump out at the reader, as do suddenly italicized lines or moves within a poem between serif and sans serif fonts. Take note of the variety of female experiences, the choices of fonts insist, even as there is much repetition in word choice and imagery throughout the book. In fact, at the bottom of the piece called “copy,” which incorporates text on top of a photocopy of hands, are the words “how does repetition affect meaning?” arranged in a tight circle, echoing the absence of beginning or ending that consciously embodies the relentlessly circling questions in this book built of recursions.

Since Dentz has professional experience working as a graphic artist, it’s no wonder that text as purposeful design element gets a lot of attention from readers and reviewers of this book alike. Nonetheless, Dentz is also a poet, so let’s not forget text as poetry. Consider these lines from the prose poem “Cabinets,” which capture the strangeness of the way aging affects self-perception, with even the workings of the mind becoming unfamiliar:

So there I was again in the familiar here-nor-there. If I had a drawbridge in my

mind, it lifted, and my thoughts couldn’t cross to meet each other. If I had arms

inside, they were flailing, waving.

Dentz concludes this poem with “Birds trilling again, whistling. / One could feel at one with wind, its motion.”, finding at last a recognition of the only possible response to the indignities of aging in the unpredictable vagaries of wind.

The aging body and the (often) resulting feelings of alienation from one’s own body are topics Dentz never shies away from, with refreshing lines such as these from “troy moon”:

movie that comes full circle no happy ending just get up and knock your chin on the door again

and again;

no money in that

soul whatever that is

chin’s raw and little hairs grow nevertheless, never to get away from this mess

Or these from “Units & Increments”:

[…] am swinging between age and youth,

trying to find a way to keep the blur rushing

towards me green and impressionistic. trying

to not lose “it.” not ready to be encased like

an iridiscent gray branch. losing your period

is like losing someone to a freak accident.

[sic]

Both of these embodied poems also contain the notion of a lack of endings, the circle with no ending and the swinging back and forth, that the many forms throughout Sisyphusina likewise suggest. The aging bodies of other species, such as whales and flounder, and of peoples at other times, including the ancient Egyptians, robustly fill out the physicality of the subject.

Moreover, the social alienation that results from being an aging woman are laid bare. Dentz sees women not being seen in the opening lines of “seasoned”: “Not being authentically original, moving. I should enjoy my nothing tree / looking at other trees. // I can become as change, or it might just be too laborious. water is no color.” Again, there is a lack of resolution haunted by the unspoken knowledge that the only resolution, the only ending to aging, to circling the drain, is death. With surprising wryness and wit, other poems grapple with the built-in constant valuations and rankings that a consumerist society place on women, particularly unflatteringly on aging women.

On top of dizzyingly original arrangements of words and forms, this collection offers artistic and musical collaborations, which are better experienced than described. Either a QR code at the end of the book or an online link will take you to the sound performance “Aging Music,” performed by Pauline Oliveras, which was co-imagined with Dentz’s Sisyphusina. Additionally, a poem-film based on Dentz’s “saidst,” jointly made with Kathy High, is available online. With so many modalities for the witnessing the exploration on women’s aging, Dentz has more than done her part to record this complicated experience, available vocabulary notwithstanding, for the future canon.

Jessica Goodfellow’s poetry books are Whiteout (University of Alaska Press, 2017), Mendeleev’s Mandala (2015), and The Insomniac’s Weather Report (2014). A former writer-in-residence at Denali National Park and Preserve, she’s had poems in The Southern Review, Ploughshares, Scientific American, Verse Daily, Motionpoems, and Best American Poetry 2018.